“An interview is like theater backwards: the interview is the performance and then you write the play.” Claudia Dreifus.

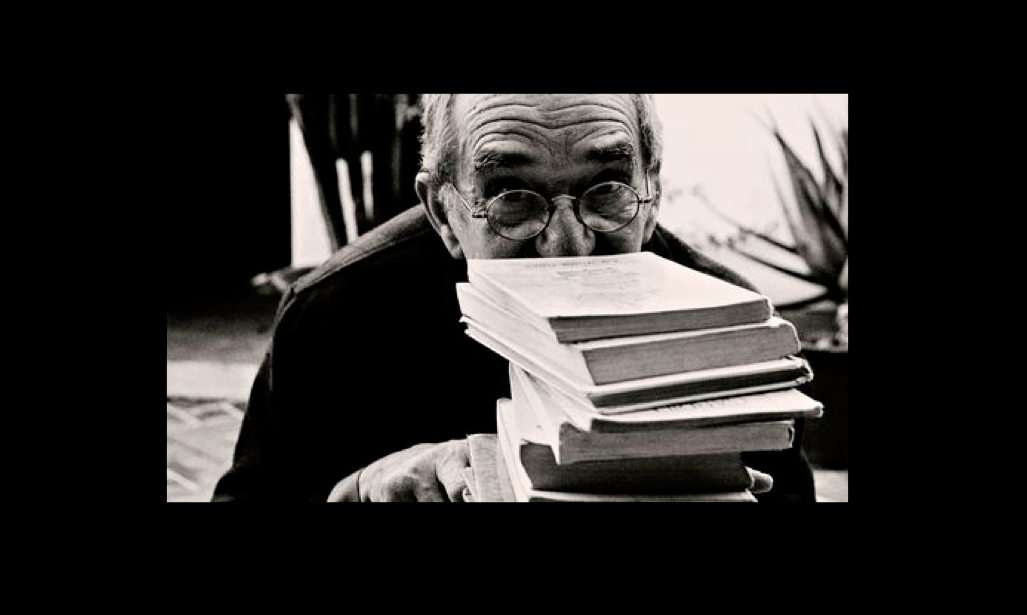

Months before receiving the literature Nobel Price in 1982, Gabriel García Márquez welcomed Claudia Dreifus in his house at Montparnasse, Paris. Dreifus, currently a New York Times journalist achieved one of the most memorable interviews with García Márquez while working for Playboy Magazine.

The interview came out in February 1983 after a several months of polemic delay from Playboy Magazine that postponed its publishing until the price was awarded.

Why do an interview with Garcia Márquez for Playboy?

For much of the 60’s through the 80’s and into de the 90’s, the Playboy interview was the premier interview in the journalistic world. There was more space to develop the form and it became an art form in and of it self. So to be in Playboy Magazine gave you both the room and the money to do things you couldn’t do anywhere else in journalism. All the important people of the time would sit for the Playboy interview. It was like a ritual. Adding to that, the people who wrote the Playboy interviews was a very elite group, some of the greatest interviewers and writers. So I was really fortunate to be among them.

How was the process of getting the interview, how did you managed convinced him?

I had done a Playboy interview with the film actor, Donald Sutherland. It was a terrific interview and then the magazine said to me, «who do you want to interview next?» I had been reading a One Hundred Years of Solitude and while having lunch with a friend we talked about it and I decided to add him to the list of people I was going to suggest. There were some movie stars, rock signers, and there was Gabo (Gabriel Garcia Márquez). When I suggested his name my editors said, «see if you can do it.»

I didn’t know anybody who knew Gabo, but I new somebody who knew his translator, Gregory Rebassa. And you always need, as I say to my students, a rabbi to connect you with the person you are looking for. It was known that he was elusive; that he didn’t give many interviews and that he was in a State Department list that made it very difficult for him to travel to the US. So I took his translator for lunch and we talked about the topics of the interview, which were his literature, the emerging Latin American literature and it’s discovery by the rest of the world.

Just by chance, for some fluky reason, Gabo came to New York and Gregory Rebassa called me and said, «you can get him on the phone.» I reached him in his hotel using a payphone –because at that time there were no cellphones. Rebassa had spoken to him about me. I think he wanted to figure out if I was worthy. Among the things we talked, he said he didn’t wanted to do the interview in English because he didn’t felt confortable enough.

So you told him you knew French?

(laughts) Not really. He asked if I know Spanish and I said no. Then he asked, “well what do you speak, besides English?” I said, “German…” and we both laughed. He said that this was beginning to sound like a Dos Passos novel. So we agreed that I would come to Paris and after eight weeks of studying as if I was studying for a doctoral degree, I met him in the french capital with my interpreter.

Were you able to see him during intimate moments or share time with his family?

He came to my hotel the first day and we talked for several hours. Then he invited us for lunch and he talked about how he knew everything about food and how you couldn’t get a bad meal in Paris. Nothing had been open so we finally ended up in one of these cafes where Sartre and De Beauvoir used to go, but it was the most atrocious and disgusting food. He had managed to find the one bad restaurant in Paris.

Did you tell him that after?

I think we all make jokes about it, but he wasn’t all that funny, which also surprised me. I found him very serious as many funny people are. People read One Hundred Years of Solitude and find it funny and charming, but he was actually very somber. So I tried to lighten the interview up and one day I went out and I bought very expensive truffles from the best truffle maker in Paris. A huge box wrapped in a pink satin ribbon and I said, “in One Hundred years of Solitude there is a priest that levitates with chocolate. Let’s see if this could make this interview levitate.” He took the box, threw it in a corner and said, “it only works with liquid chocolate, as it was written on the book.”

Was there any moment when he opened himself up to you?

He opened himself up pretty much throughout the interview. He said his son had asked him to do the Playboy interview. He told me the background of every story in One Hundred Years of Solitude–all the real stories behind the mythical ones. One of the things he told me is that among his friends he was the most practical person, and that he also possessed almost clairvoyance of accidents and bad things happening around him. As he was telling me this, a painting fell to the floor. I asked him if he predicted that, and he said, “no, that is just an accident.

You make reference in your interview to his close relationship with Panamanian dictator, Omar Torrijos and Fidel Castro. Where you able to identify the obsession, some have said, that he had for power?

I think he was interested in the powerful and their impact in Latin America. Like many Latin-American writers, he wrote at least one novel about a dictator. That seemed to be a ritual. But I didn’t particularly feel that. I think he was very confident in his skills as a writer. One Hundred Years of Solitude is probably the greatest piece of Spanish literature since Cervantes.

What he did was powerful in a different sense: he told the Latin American story in Latin American terms as an insider.

Now you ask about his friendships. I don’t know how genuine it was when he said that his friendship with Castro was just personal. Castro is an interesting person, so he might have found him intriguing. They were just a bunch of great guys who liked each other. Although, let me add the term great guys in quotes, I mean they had like guy friendships and they must of been very interesting to each other. But I don’t think it was because he was that interested in power perse.

Gabo once asked the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, if journalism was the way to connect writers back to reality. You mention in your interview that Garcia Márquez’s goal was to find a connection between journalism and literature. Do you think that is what differentiated him from other writers of his time?

He would take reality and just move it one step into outer space. He just moved reality a little, but in a very believable way so you believed that butterflies entered the room every time people were in love. What he would do is tell amazing things that you wouldn’t quite believe but he would tell them with such a straight face that you would.

In past interviews Gabo mentions that love drove his desire to write. Where you able to identify this in your interview?

Yes, he ended the interview that way and he certainly was loved. People all over the world loved him and felt One Hundred Years of Solitude was their own story. Koreans and Japanese would find it fascinating because there was a kind of universality to the family story. People see their own families in his characters. He changed our perception of Latin American Literature and opened the way for other Latin American literature to develop. He certainly paved the way to people like Julio Cortázar and Carlos Fuentes. It’s not that these writers didn’t have readers in their own countries; it’s just that people through Europe and the United Stares began looking at Latin America with literary respect and fascination after Gabriel García Márquez.

I had a professor who said once that Gabo received the Novel Price because he described a culture. Do you think this is true?

I think he just moved the entire culture forward, and he created great literature about a culture. A lot of the literature in the developing world had difficulties being seen and appreciated in the developed world. He brought Latin America to everyone. So I don’t think he got the Nobel Prize for that reason. I think he had the Nobel because he was a great artist and his literature needed recognition.

Gabo said once that to be a good writer you have to be a good journalist. To be a good journalist do you need to be a good writer?

No, the opposite isn’t true. I think that to be a good novelist, whatever you write has to be believable, unless you are a non-fiction novelist. To be a good journalist you have to be factual, truthful, reliable, observant and good writer. That’s a lot. I think it might even be harder than being a writer because you have to make it all work and you can’t adjust reality a little bit.

Many compare you with Oriana Fallaci, who was considered one of the greatest interviewers of the last century. Can you share with us some secrets about your interviewing techniques?

I compensate with my shyness by being extremely well prepared in my interviews, and I advice anybody to do the same. Then I kind of let go improvising from the basis of being well prepared. The other thing is that I chose my interview subjects very well. I don’t interview just anybody simply because they are famous or powerful, I interview them because I sense they are good storytellers.