The street lay deserted. It was six in the morning. Intermitent rain. My grandfather woke up that morning earlier than usual. He had a pending commitment. The railroad employees were awaiting him, filled with anxiety and euphoria. They had assembled on a street in downtown Güemes, in the province of Salta.

They walked as a group. They yanked the dry branches from the orange trees that lined the sidewalks, and littered the streets with pamphlets swollen with insulting words. They painted the walls with slogans they’d been repeating for months against the government and they gathered signatures from among the people in the streets on their way to work.

At eight a.m. they built an improvised stage with boards they’d brought from the train station. My grandfather stood up on the slippery wood. He had white, pink hands (because he was an Italian immigrant, as the train workers would say) and he held a piece of paper with some words he’d thrown together.

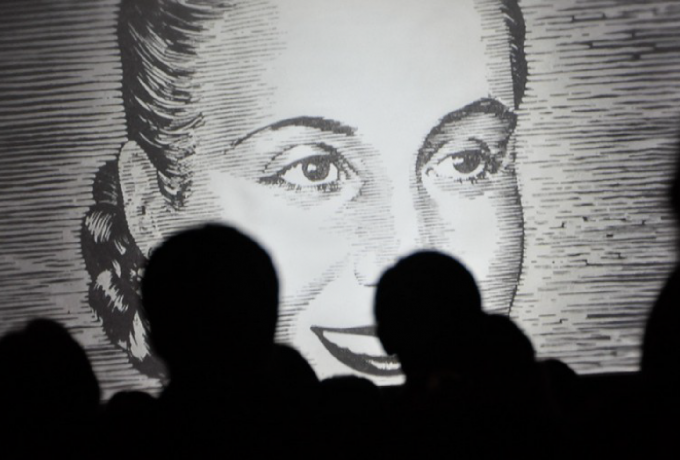

The children silently crossed the courtyard of the little schoolhouse of that town in Salta. My mother, sporting her bangs and the little earrings she always wore, walked among the young school girls. They’d announced on the radio that the spiritual leader of the nation had died. My mother couldn’t make sense of any of it.

My grandfather had already left for his meeting with the railroad workers. The teachers, all women, walked over to the little girls and placed a black band on their right sleeve. A blond teacher, her hair bun firmly in place in conformance with the official style, approached my mother and fastened the narrow black band to her sleeve.

My grandfather was the union representative for the railroad workers. The workers had elected him unanimously. He had been persecuted by the Peronists and he had raised his voice on many other occasions addressing people who didn’t listen to him.

He stood up on the damp and slippery boards. He swallowed hard. He spoke a few sentences, and received the warm applause of his fellow workers.

My grandfather was a man of few words. Generally he just listened. When he did speak it was always to demolish his opponent. While the other would be spouting the clichés of the official line, his face, which was white and pink, would be turning a dark rosy color, almost violet, until it turned red. His eyes would glow like two lanterns in the dark of night and then, after the enemy lips had finished spewing spit, my grandfather’s mouth would bring forth that collection of syllables that seemed like a bullet he’d been preparing for years.

The strident bleat of a trumpet swept over the little schoolhouse’s courtyard laid out like a checkerboard. The principal asked for a minute of silence. Only the song of a bird inte1rrupted the obedient gesture on the part of all of the schools in the country. A few innocent giggles floated in the air. One of them belonged to my mother. She pinched the cheek of the girl next to her and the latter tickled her arm. My mother laughed and covered her mouth. But it was too late. The sharp sound of her laughter slipped through the hand my mother had covered her mouth with, dispersing in the gloomy morning courtyard. The teacher with the bun went over to my mother and rapped her on her head with her knuckles.

While my grandfather was reading his speech, a man climbed up on the wet stage and whispered some words in his ear. My grandfather suddenly interrupted what he was saying and looked at those present, yelling at the top of his voice. Evita has died! Immediately all the workers began to cheer. My grandfather tossed aside the piece of paper with its few words and lowering his arm, taking out the revolver he’d slipped into his pants pocket and fired a shot that rang out. Then he said “Long live Argentina!”

The little girl who was my mother cried out in pain in the checkerboard courtyard. Although the blow hadn’t been all that bad, her voice pierced the ears of the teachers. Less out of pain than of caprice, she yelled out as if they’d slashed her ear.

The shot from the stage became lost in the cloudy sky. No one suspected that my grandfather’s shot coincided, at the precise moment, with my mother’s yowl of pain in the courtyard of the little schoolhouse in that town of Salta.

Translated from the Spanish by David William Foster

(Mother: the brief life of Soledad H. Rodriguez, Culiquitaca, 2013)

Photo Credits: Víctor Santa María